VMProtect - From scratch!

Intro - VMProtect

According to the official VMProtect website (VMProtect Software) VMProtect is designed to “secure your code against reverse engineering, analysis, and cracking. Use the advantage of code virtualization, which executes virtualized fragments of code on several virtual machines embedded into the protected application.”

VMProtect is a virtualization-based software protection system. What makes it unique is its ability to generate custom virtual instruction sets for every build. This means that no two protected binaries are the same each one uses a completely different virtual architecture. Additionally, VMProtect can mix native and virtual instructions within a single function, making static analysis and devirtualization significantly more difficult.

- Note: In general, VMProtect is designed for both personal and commercial use, and you can find it in many games today. However, it can also be used in malware due to its strong protection. One of the main weaknesses of this protection is its impact on performance, as the bytecode handling can slow down execution.

Software Virtualization

Software virtualization, in the context of code protection, is different from operating system or hardware virtualization. Instead of emulating an entire system or memory layout, software virtualization transforms CPU instructions into custom bytecode, which is then executed by a virtual machine embedded in the application. This “virtual machine” uses handler functions that interpret and execute each bytecode instruction, effectively hiding the original logic from disassemblers and reverse engineers.

example

Let’s take a look at this sample bytecode handler:

#include <stdio.h>

uint8_t bytecode[] = {

0x01, 3, // PUSH 3

0x01, 5, // PUSH 5

0x02, // ADD

0x03, // PRINT

0xFF // HALT

};

int main() {

int stack[16], sp = -1;

for (int ip = 0; bytecode[ip] != 0xFF; ) {

switch (code[ip++]) {

case 0x01: stack[++sp] = code[ip++]; break; // PUSH

case 0x02: stack[sp-1] += stack[sp--]; break; // ADD

case 0x03: printf("%d\n", stack[sp--]); break; // PRINT

case 0xff: while(1){}; // HALT

}

}

return 0;

}

let’s break it down, this handler creates its own stack and stack pointer, then uses a switch statement to handle each bytecode instruction. Each opcode performs a specific function, like pushing a value / adding two values / printing the result. In other words, it simulates a tiny virtual CPU!

Analyzing a Real Handler

Now we’re going to begin our first analysis mission! We’ll start with a simple binary that I compiled myself using the VMProtect demo version (just for learning purposes). You can download the binary here. As we’ve learned, each build of VMProtect generates a unique virtualization protection, so I recommend using this specific binary. If you want to try compiling your own binaries with VMProtect, you can download the demo version installer from here.

The binary source is:

#include <stdio.h>

int func(int x, int y) {

return x ^ y;

}

int main(void) {

int x, y;

printf("xor nums <x y>: ");

scanf("%d %d", &x, &y);

printf("result: %d", func(x, y));

return 0;

}

And the exe file before the VMProtect build is Source exe.

Let’s dive into the analysis of the Protected binary.

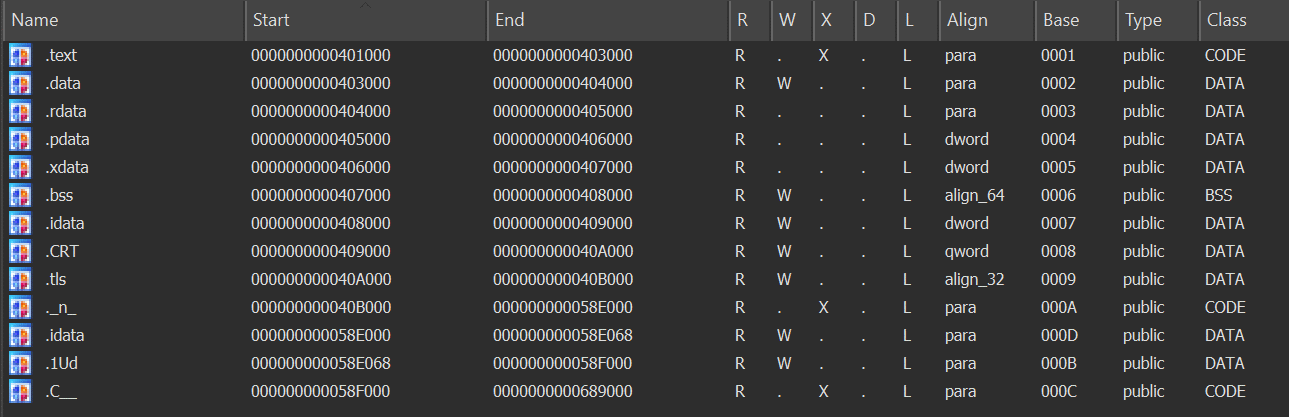

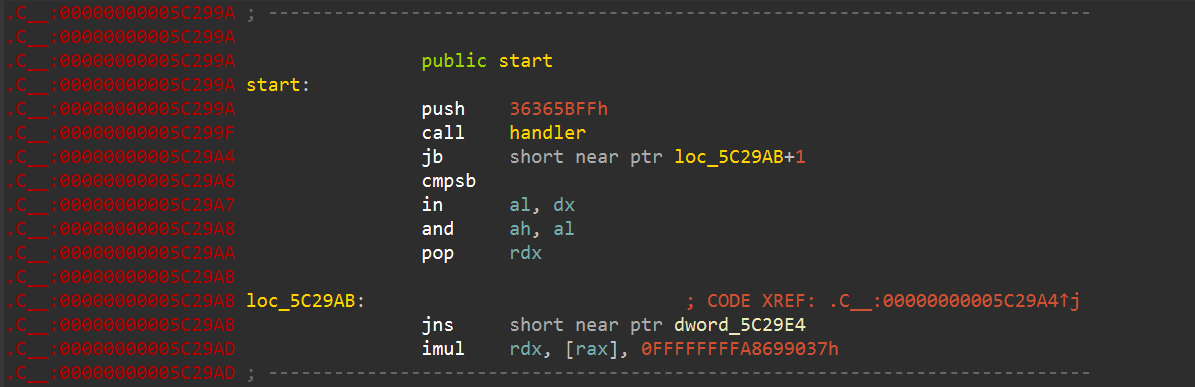

- Note: I’m using IDA-Pro V7.6 First, we should take a look at the segments in the binary and identify which one contains our code.

At first, we might think the code is in the .text segment, but if we check what’s actually in that segment, we’ll see this:

This segment doesn’t contain typical code instructions.

Instead, it’s mostly filled with uninitialized data (indicated by dup(?)) and includes named entries like TlsCallback_1 and TlsCallback_2. These are Thread Local Storage (TLS) callbacks - standard Windows mechanisms that execute before the programs actual entry point.

They are not specific to VMProtect, but they are often used in packed or protected binaries as part of the init process.

This strongly suggests that the real code has been moved or hidden elsewhere, most likely in a custom section created by VMProtect, where the actual logic is either encrypted, packed, or virtualized. So, let’s identify the entry point of the binary.

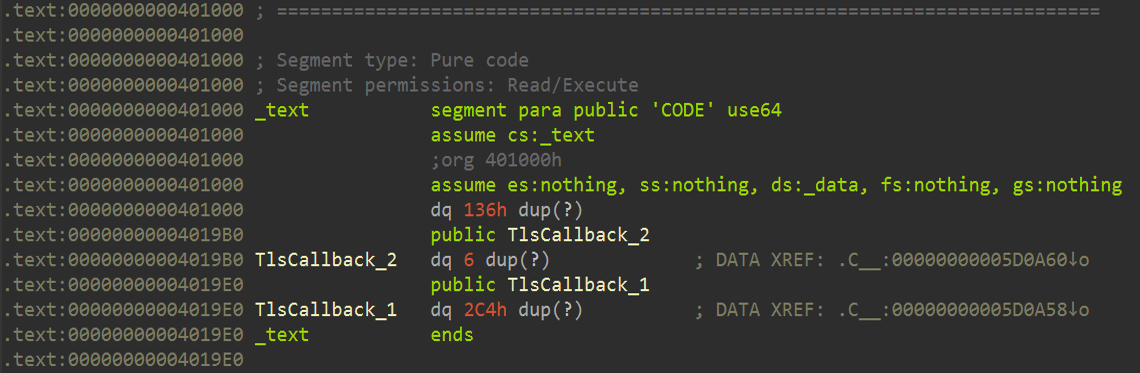

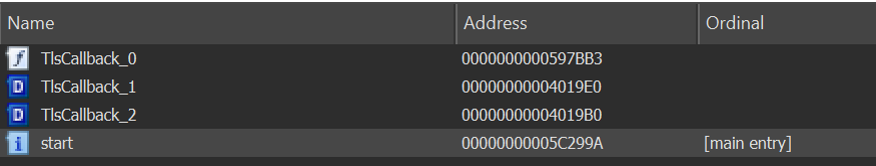

Now let’s see which segment actually contains the entry point:

Here we can see that the entry point is located in the .C__ segment, This segment was created by VMProtect and contains the call to the VMProtect handler.

The handler’s code, after being decompiled using the Hex-Rays decompiler, is as follows:

void __fastcall bytecode_handler(

_WORD *bytecode, __int64 param1, __int64 param2, __int64 param3,

int op1, int op2, int op3, int op4, int op5, int op6, int op7,

int op8, int op9, int op10, int op11, int op12, int op13) {

__int64 saved_rax;

__int64 saved_r10;

__int64 saved_r11;

__int64 saved_r14;

_WORD *current_opcode_ptr; // pointer to the current opcode

unsigned __int8 *bytecode_ptr; // pointer to the bytecode stream

int *stack_pointer; // stack pointer (rsp)

int *operation_ptr; // pointer to the current operation in stack

__int64 operation_data; // operation data var

_BYTE stack[248]; // virtual stack buffer

*(_QWORD *)&stack[72] = saved_r10;

*(_QWORD *)&stack[56] = saved_r11;

*(_QWORD *)&stack[48] = saved_r14;

*(_QWORD *)&stack[40] = param3;

*(_QWORD *)&stack[24] = param2;

*(_QWORD *)&stack[8] = __readeflags(); // save flags

stack_pointer = (int *)stack; // init stack pointer

*(_QWORD *)&stack[80] = 0; // clean stack space

bytecode_ptr = (unsigned __int8 *)(1 - _byteswap_ulong(~(*(_DWORD *)&stack[128] + 1)) - 2);

LODWORD(operation_ptr) = __ROR4__((unsigned __int16)bytecode, 49); // Rotate bytecode

while (1)

{

_AX = *bytecode_ptr;

WORD1(operation_ptr) &= WORD1(bytecode_ptr);

_BitScanReverse((unsigned __int16 *)&operation_ptr, param3);

++bytecode_ptr; // move to next byte

// handle the operation based on the opcode value

switch ((int)operation_ptr)

{

case 0:

// Opcode 0: simulate a stack push operation

current_opcode_ptr = (_WORD*)stack_pointer;

operation_ptr = (int *)*((_QWORD *)stack_pointer + 1); // get next stack value

stack_pointer += 4;

*(_QWORD *)current_opcode_ptr = operation_ptr;

continue;

case 1:

// Opcode 1: perform a bitwise rotate and store value in memory

current_opcode_ptr = *(_WORD **)stack_pointer;

__asm { rcr ax, 6 } // rotate right

_WORD result = *((_WORD *)stack_pointer + 4);

stack_pointer = (int *)((char *)stack_pointer + 10); // move stack pointer

*current_opcode_ptr = result;

continue;

case 2:

// Opcode 2: store a value from bytecode into a specified memory location

current_opcode_ptr = *(_WORD **)stack_pointer;

stack_pointer += 2;

operation_data = *(unsigned __int16 *)bytecode_ptr; // get data

bytecode_ptr += 2;

*(_QWORD *)&stack[operation_data] = current_opcode_ptr; // store the value at specified location

continue; // Continue to next opcode

case 3:

// Opcode 3: perform a complex bitwise operation and update stack

int op_result = *stack_pointer;

__asm { rcr cl, 23h } // rotate right

LOBYTE(bytecode) = *((_BYTE *)stack_pointer + 4);

_BL = *stack_pointer;

stack_pointer = (int *)((char *)stack_pointer - 6);

__asm { rcl bl, 8Eh } // Rotate left

stack_pointer[2] = op_result << (char)bytecode;

*(_QWORD *)stack_pointer = __readeflags(); // save flags

goto stack_adjust; // jump to `stack_adjust` label

case 4:

// Opcode 4: Handle an operation and update the stack

operation_data = *(unsigned __int16 *)bytecode_ptr;

_R9 = -99; // Set special register

bytecode_ptr += 2; // Move bytecode pointer by 2 bytes

__asm { rcr r9b, cl } // Rotate right

LODWORD(param3) = *(_DWORD *)&stack[operation_data];

*--stack_pointer = param3; // Push data to stack

stack_adjust:

// stack adjustment and flag handling

operation_ptr = &op13;

if (stack_pointer <= &op13)

{

operation_ptr = (int *)(((unsigned __int64)(stack_pointer - 32) & 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0) - 256);

bytecode_ptr = bytecode_ptr;

v23 = __readeflags();

qmemcpy(operation_ptr, stack, 0x100ui64); // copy data from stack

LOBYTE(bytecode) = 0;

__writeeflags(v23); // Restore flags

}

break;

default:

// default case: Jump to an invalid opcode handler (block opcodes modifying)

JUMPOUT(0x682329i64);

}

}

}

Handler opcodes:

- Opcode 0: Simulates a stack push — copies a value from the virtual stack and writes it back to memory.

- Opcode 1: Performs a bitwise rotation and stores a 16-bit value into a memory location pointed by a stack value.

- Opcode 2: Reads a 16-bit offset from bytecode and writes a pointer (from the stack) into that offset in the local stack buffer.

- Opcode 3: Executes bitwise shifts and rotates, modifies values using bit operations, and updates stack with the result.

- Opcode 4: Loads data from a calculated offset, does a bit rotate on a register, and pushes the result onto the virtual stack.

- Default: Handles invalid or unknown opcodes by jumping to an error or obfuscation routine.

VMProtect uses this handler and its opcodes to interpret and execute virtualized bytecode that works like the original software’s logic. This allows the program to run “normally” while making reverse engineering extremely difficult, since the actual instructions are hidden behind a custom virtual machine rather than standard CPU code.

Performance

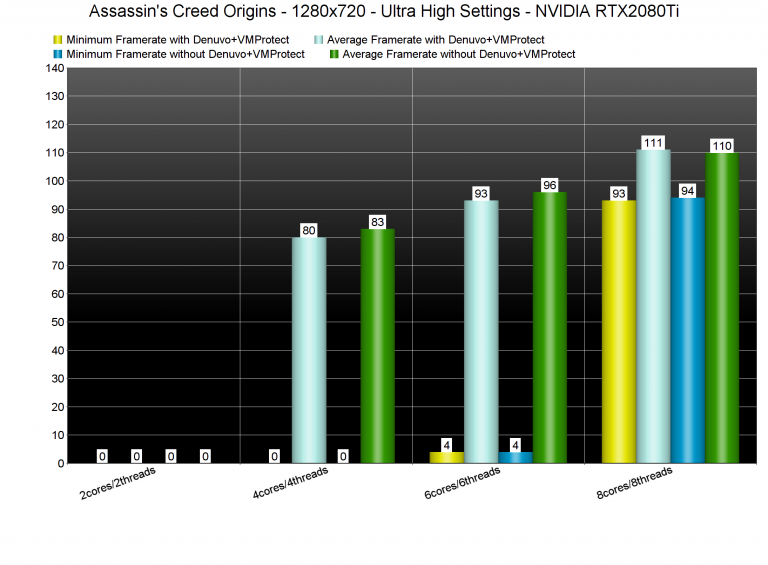

In games, VMProtect is often combined with other DRM protections. One of the most well-known examples is Assassin’s Creed, which used both VMProtect and another complex DRM system called Denuvo (which also uses virtualization-based techniques). Below is a graph comparing the frame rates (FPS) of the game in both scenarios — with and without that protections:

We can see that these protections really hurt the game’s performance, and that’s why a lot of players are upset with the game companies.

Malwares

Malware authors often use VMProtect to make their code harder to analyze and reverse engineer. By wrapping malicious code in layers of virtualized instructions, VMProtect can hide the real behavior of the malware from static and dynamic analysis tools. This makes it difficult for security researchers to understand what the malware does or to write effective detections. While VMProtect was originally designed to protect legitimate software, its strong obfuscation and virtualization features have made it attractive to attackers trying to avoid detection.

examples

- LokiBot - info-stealer that have been found using VMProtect to hide its payloads.

- FinFisher (also known as FinSpy) - spyware that has used VMProtect to make reverse engineering harder. These cases show how a tool made for software protection can be repurposed by threat actors to shield their malicious operations.